| About |

| The Results Wave 28 Wave 27 Wave 26 Wave 25 Wave 24 Wave 23 Wave 22 Wave 21 Waves 11-20 Waves 1-10 |

| Working Paper Series |

| Related Research |

| Authors |

| Sponsors |

| FAQ |

| Contact |

| Press Room |

|

The Results: Wave 1

Paola Sapienza and Luigi Zingales1 January 27, 2009 - If a modern Rip Van Winkle had fallen asleep two years ago and woken up now, he would wonder what had happened to the U.S. economy. Two years ago, we were in the middle of an economic boom. Banks were eager to lend even at the cost of forgoing important covenants, and corporate America (and the entire world) was producing at full steam, so much so that commodities prices were rising in anticipation of a future scarcity. Today we are quickly sliding into a deep recession. Banks are not lending and commodity prices are plummeting in expectation of a dramatic slowdown of production throughout the world. Everyone agrees that this crisis originated in the financial system. When Lehman Brothers defaulted and AIG had to be rescued by the government in September, the economy was still doing all right. The rate of growth during the second quarter was still a comfortable +2.8 percent. How could the default of an investment bank, with very limited lending to the real economy, have had such a disastrous effect? The Missing Link Trust is our expectation that another person (or institution) will perform actions that are beneficial or at least not detrimental to us, regardless of our capacity to monitor those actions.2 When we say we trust someone, we imply that we think that he will engage in beneficial, non detrimental action so that we’ll consider cooperating with him. While trust is fundamental to all trade and investment, it is particularly important in financial markets, where people depart with their money in exchange for promises. Promises that aren’t worth the paper they’re written on if there is no trust. In previous research we showed that trust can explain households’ investment in the stock market and international portfolio investments (Guiso, Sapienza, Zingales, 2004 and 2008). To study how recent events have undermined Americans’ trust in the stock markets and institutions in general, we conducted a survey. The Financial Trust Index

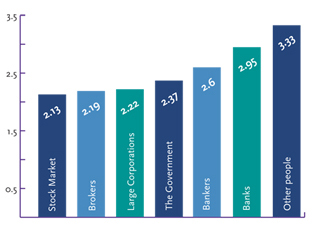

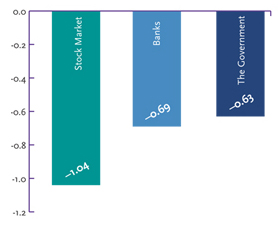

Social Science Research Solutions was commissioned to conduct a telephone survey on a representative sample of 1,034 American households from December 17 to 28 2008.3 One adult respondent in each household was randomly contacted and asked whether they were in charge of household financial, either alone or together with the spouse. Only individuals who claimed such responsibility are included in the survey. The first set of questions asked how much people trust certain types of people or institutions, on a scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 means “I do not trust at all” and 5 means “ I trust completely.” Figure 1 reports the results. On average, people trust “other people” the most (3.33), followed by banks (2.95), then bankers (2.60), then the government (2.37), then large corporations (2.22), and finally the stock market (2.13). But this ranking is not just reflecting risk aversion. We asked respondents to answer a simple question proven to be a good proxy for risk. The top 25 percent, the people most comfortable with risk, showed exactly the same trust rankings as the entire sample. Why does trust in some types of institutions (or people) suffer compared to trust in “other people” in general? Either the sub-type of people working in those institutions must be considered worse than the average person, or the institutions themselves must be thought to have negative effects on individuals. Bankers, for instance, are considered less trustworthy human beings than people in general (2.65 vs. 3.33). Banks, however, are more trustworthy than bankers (2.95 vs. 2.60), suggesting that the incentive structure within banks is believed to moderate the lack of trustworthiness of bankers. The same cannot be said for the stock market. Brokers are considered less trustworthy than bankers (2.19 vs. 2.60), but the stock market is considered as trustworthy as brokers (2.13 and 2.19). Ideally, one would like to analyze a series of surveys conducted over time to see, for example, how recent events affected trust in the stock market. Unfortunately, such time-series data do not yet exist. So we tried to elicit self-assessed change by asking people how much their level of trust changed in the last three months. Respondents were asked, “How has your trust in some of these institutions changed in the last three months?” The scale ranged from -2 to +2, with -2 meaning “Decreased a lot, -1 meaning “Decreased a little,” 0 indicating no change, and +1 or +2 indicating a little or a lot of increase.

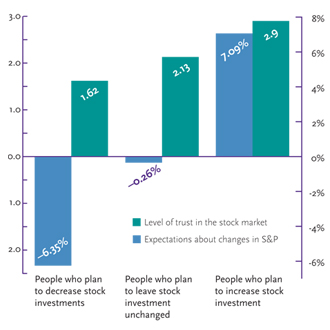

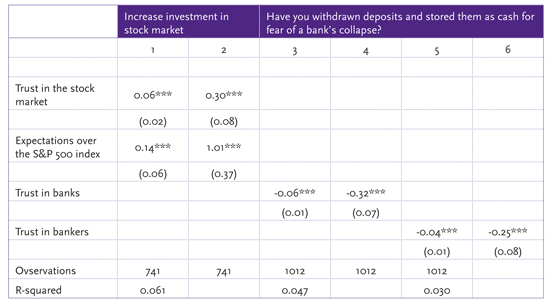

Effects of trust Trust affects people’s intention to buy stocks even after we account for their expectations of stock market performance. Respondents were asked how much they expected the S&P 500 to increase or decrease in value in the following year. Thirty-two percent of the respondents expect a negative return, 37 percent a positive return, and 31 percent expect a return exactly equal to zero. As expected, willingness to increase investments in stocks depends on whether an individual expects the market to rise or fall. But trust has a significant, positive effect on the intention to increase investment after controlling for the expectations (see Figure 3 and Table 1 in the Appendix).

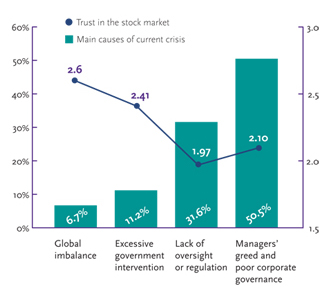

We obtain very similar results if we regress the decision to buy/sell stock on the changes in the trust in the stock market and the level of expected return of the S&P in the following 12 months. Both variables have a positive and statistically significant effect. Similarly, the decision to withdraw deposits and store them as cash for fear of a bank’s collapse (an action taken by 11 percent of the sample) is related to trust in banks and bankers. Trust in financial institutions and markets has dropped significantly over the last three months, explaining the intention to sell stock and withdraw deposits for fear of a bank’s collapse. Changes in trust matter. But what causes the changes? What Determines Trust? Thus disappointment over short-term performance is one of the channels through which a stock market crisis becomes a trust crisis. To further explore the connection between the loss of trust and various events occurring during this period, we correlated levels changes of trust with the feelings respondents expressed about several key policy issues. Respondents were first asked what they felt was the main cause of the 2008 financial crisis. They were provided with six possible answers ranging from managers’ greed (the top choice with 36 percent of the responses) to excessive government intervention (11.2 percent), from lack of oversight (16%) to poor corporate governance (15 percent), and from lack of regulation (15 percent) to global imbalances (6.7 percent). The order in which the six possible answers were provided was randomized to eliminate any possible interviewer bias. People who think that the main cause of the crisis was managers’ greed were grouped together with people who attribute the crisis mostly to poor corporate governance. Similarly, we grouped together people who think that the main cause of the crisis is lack of oversight and those who think it is lack of regulation.

As Figure 4 shows, people who attributed the crisis to global imbalances retain much higher trust in the stock market (2.6). The same is true for those who blame excessive government intervention (2.41). The lowest level of trust was among people who thought that the crisis was due to lack of oversight and lack of regulation (1.97). A similarly low level of trust in the stock market was present among people who thought that the crisis was due to managers’ greed or bad corporate governance (2.10). Lack of trust appears to be pervasive among people who are worried about bad corporate governance and lack of government intervention. These people also exhibit a bigger reduction in trust in the last few months.

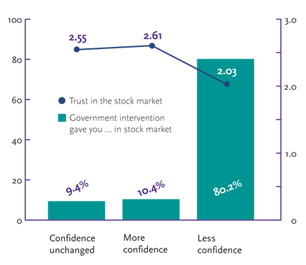

There is an apparent contradiction in that 32 percent blamed the crisis on lack of government intervention, while 80 percent are made less confident in the stock market by the government intervention. Are we dealing with two sets of people with different political views? Or, did those in support of government intervention not like the way the government intervened?

To disentangle these two possibilities we used two additionalquestions. One asked the interviewees whether they thought the government should intervene to regulate the financial sector more. Among the 55 percent who think the government should intervene more, 75 percent were made less confident by the government intervention in the last few months. Among the 45 percent who think the government should not intervene, 85 percent were made less confident by the government intervention. Thus, a slight majority were predisposed to accept government intervention, but even among them, the overwhelming majority were made less confident by the way the government intervened over the last few months.

Conclusions 1 Paola Sapienza is a Professor of Finance at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University and Luigi Zingales is the Robert McCormack Professor of entrepreneurship and finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. 2 This definition is taken from Gambetta (2000). 3 The survey was conducted using ICR's weekly telephone omnibus service. It used a fully replicated, stratified, single-stage random-digit-dialing sample of landline telephone households References Appendix

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||